# Given an MSA column, return the most common element if it is at least as frequent as threshold

def find_conserved(column, threshold):

counter = Counter(column)

mode = counter.most_common(1)[0]

if (mode[0] != '-' and mode[1] / len(column) >= threshold):

return mode[0]

return NoneIntroduction

The ribosome is present in all domains of life, though exhibits varying conservation across phylogeny. It has been found that, as translation proceeds, the nascent polypeptide chain interacts with the tunnel, and as such, tunnel geometry plays a role in translation dynamics and resulting protein structures1. With advances in imaging of ribosome structure with Cryo-EM, there is ample data on which geometric analysis of the tunnel may be applied and therefore a need for more computational tools to do so2.

Background

In order to preform geometric shape analysis on the ribosome, we must first superimpose mathematical definitions onto this biological context. Among others, one way of defining shape mathematically is with a set of landmarks. A landmark is a labelled point on some structure, which, biologically speaking, has some meaning. After removing the effects of translation, scaling, and rotation, sets of landmarks form a shape space, on which statistical analysis may be applied.

Assigning landmarks to biological shapes is not a new idea; many examples involve defining landmarks as joins between bones or muscles, or as points along observed curves3. However, there has been little work in assigning landmarks to biological molecules, and none specifically to the ribosome exit tunnel. The challenge is that any one landmark must have comparable instances across shapes in the shape space, meaning that we cannot arbitrarily pick residues which we know to be near to the tunnel. Such residues must be conserved, and therefore present in each specimen, to be considered useful.

Protocol

Below, I present a preliminary protocol for assigning landmarks to eukaryotic ribosome tunnels. The goal is to extrapolate to bacteria and archaea, as well as produce a combined dataset of landmarks which spans the kingdoms for inter-kingdom comparison. For now, I begin with eukaryota, taking advantage of the high degree of conservation between intra-kingdom ribosomes, as conserved sequences form the basis for this protocol.

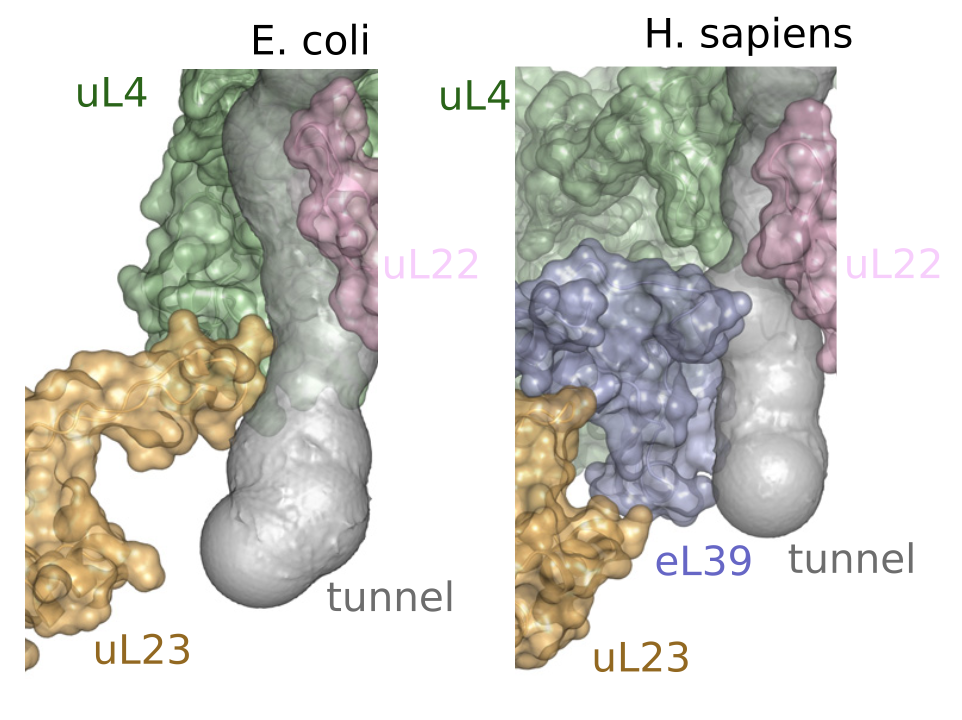

As the goal for this dataset is to obtain landmarks that line the ribosome exit tunnel, I begin by selecting proteins and rRNA which interact with the tunnel: uL4, uL22, eL39, and 25/28S rRNA for Eukaryota1.

The full protocol is available here.

1. Sequence Alignment

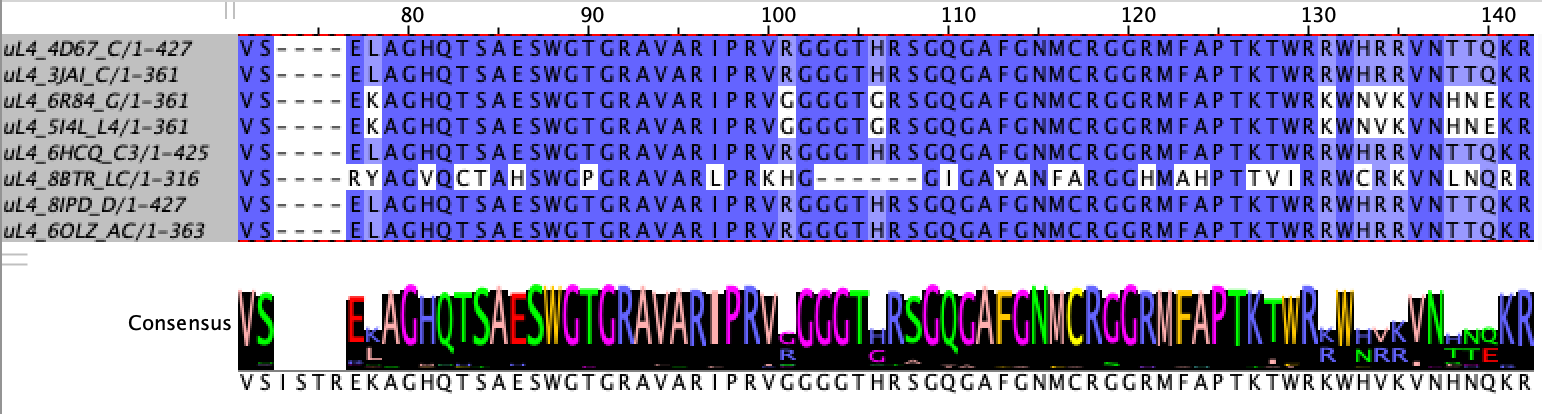

In order to assign landmarks which are comparable across ribosome specimens, I consider only the residues which are mostly conserved across our dataset of approximately 400 eukaryotes. To do so, I run Multiple Sequence Alignment (MSA) using MAFFT4 on the dataset for each of the chosen four polymer types and select residues from the MSA which are at least 90% conserved across samples.

Selecting the most conserved residue at each position in the alignment:

2. Locating Residues

To locate the conserved residues, I first map the chosen loci from the MSA back to the corresponding loci in the original sequences:

import Bio

from Bio.Seq import Seq

def map_to_original(sequence: Seq, position: int) -> int:

'''

Map conserved residue position to orignal sequence positions.

'sequence' is the aligned sequence from MSA.

'''

# Initialize pointer to position in original sequence

ungapped_position = 0

# Iterate through each position in the aligned sequence

for i, residue in enumerate(sequence):

# Ignore any gaps '-'

if residue != "-":

# If we have arrived at the aligned position, return pointer to position in original sequence

if i == position:

return ungapped_position

# Every time we pass a 'non-gap' before arriving at position, we increase pointer by 1

ungapped_position += 1

# Return None if the position is at a gap

return NoneThen using PyMol5, retrieve the atomic coordinates of the residue from the CIF file. To obtain a single landmark per residue, I take the mean of the atomic coordinates for each residue as the landmark.

Below is example code for retrieving the atomic coordinates of W66 on 4UG0 uL4:

from pymol import cmd

import numpy as np

from Bio.SeqUtils import seq3

# Specify the residue to locate

parent = '4UG0'

chain = 'LC'

residue = 'W'

position = 66

if f'{parent}_{chain}' not in cmd.get_names():

cmd.load(f'data/{parent}.cif', object=f'{parent}_{chain}')

cmd.remove(f'not chain {chain}')

select = f"resi {position + 1}"

atom_coords = []

cmd.iterate_state(1, select, 'atom_coords.append((chain, resn, x, y, z))', space={'atom_coords': atom_coords})

if (len(atom_coords) != 0 and atom_coords[0][1] == seq3(residue).upper()):

vec = np.zeros(3)

for coord in atom_coords:

tmp_arr = np.array([coord[2], coord[3], coord[4]])

vec += tmp_arr

vec = vec / len(atom_coords)

vec = vec.astype(np.int32)

print(f"Coordinates: x: {vec[0]}, y: {vec[1]}, z: {vec[2]}")3. Filtering landmarks by distance

Among the conserved residues on the selected polymers, many will be relatively far from the exit tunnel and not have any influence on tunnel geometry. Thus, I select only those residues which are close enough to the tunnel. In this protocol, a threshold of \(7.5 \mathring{A}\) is applied.

This process is done by using MOLE 2.06, which is a biomolecular channel construction algorithm. The output is a list of points in \(\mathbb{R}^3\) which form the centerline of the tunnel, and, for each point on the centerline, a tunnel radius.

Using the MSA, I locate the coordinates of the conserved residues (see Section 3.2). For each of the residues, find the closest tunnel centerline point in Euclidean space, and compute the distance from the residue to the sphere given by the radius at that centerline point. If this distance is less than the threshold, this conserved residue is close enough to the tunnel to be considered a landmark.

For efficiency, I only run the MOLE algorithm on one ‘prototype’ eukaryote to filter the landmarks, then use this filtered list as the list of landmarks to find on subsequent specimens.

Below is the code which checks landmark location against the tunnel points:

import numpy as np

def get_tunnel_coordinates(instance: str) -> dict[int,list[float]]:

if instance not in get_tunnel_coordinates.cache:

xyz = open(f"data/tunnel_coordinates_{instance}.txt", mode='r')

xyz_lines = xyz.readlines()

xyz.close()

r = open(f"data/tunnel_radius_{instance}.txt", mode='r')

r_lines = r.readlines()

r.close()

coords = {}

for i, line in enumerate(xyz_lines):

if (i >= len(r_lines)): break

content = line.split(" ")

content.append(r_lines[i])

cleaned = []

for str in content:

str.strip()

try:

val = float(str)

cleaned.append(val)

except:

None

coords[i] = cleaned

get_tunnel_coordinates.cache[instance] = coords

# Each value in coords is of the form [x, y, z, r]

return get_tunnel_coordinates.cache[instance]

get_tunnel_coordinates.cache = {}

# p is a list [x,y,z]

# instance is RCSB_ID code

def find_closest_point(p, instance):

coords = get_tunnel_coordinates(instance)

dist = np.inf

r = 0

p = np.array(p)

for coord in coords.values():

xyz = np.array(coord[0:3])

euc_dist = np.sqrt(np.sum(np.square(xyz - p))) - coord[3]

if euc_dist < dist:

dist = euc_dist

return distFinally, plotting the results using PyMol:

For information on the mesh representation of the tunnel used in the figure above, see ‘3D tesellation of biomolecular cavities’.

Notes

The code in the post uses a package (

pymol-open-source) which cannot be installed into a virtual environment. I have instead included a/ymlfile specifing my conda environment that is used to compile this code.The code used to retrieve atomic coordinates from PyMol is not robust to inconsistencies in CIF file sequence numbering present in the PDB. My next steps for improving this protocol will be to improve the handling of these edge cases.