Introduction

Multidimensional scaling (MDS) is known to be sensitive to such orthogonal outliers, we present here a robust MDS method, called DeCOr-MDS, short for Detection and Correction of Orthogonal outliers using MDS. DeCOr-MDS takes advantage of geometrical characteristics of the data to reduce the influence of orthogonal outliers, and estimate the dimension of the dataset. The full paper is available at Li et al. (2023).

Background

Multidimensional scaling (MDS)

MDS is a statistical technique used for visualizing data points in a low-dimensional space, typically two or three dimensions. It is particularly useful when the data is represented in the form of a distance matrix, where each entry indicates the distance between pairs of items. MDS aims to place each item in this lower-dimensional space in such a way that the distances between the items are preserved as faithfully as possible. This allows complex, high-dimensional data to be more easily interpreted, as the visual representation can reveal patterns, clusters, or relationships among the data points that might not be immediately apparent in the original high-dimensional space. MDS is widely used in fields such as psychology, market research, and bioinformatics for tasks like visualizing similarities among stimuli, products, or genetic sequences (Carroll and Arabie 1998; Hout, Papesh, and Goldinger 2013).

Orthogonal outliers

Outlier detection has been widely used in biological data. Sheih and Yeung proposed a method using principal component analysis (PCA) and robust estimation of Mahalanobis distances to detect outlier samples in microarray data (Shieh and Hung 2009). Chen et al. reported the use of two PCA methods to uncover outlier samples in multiple simulated and real RNA-seq data (Oh, Gao, and Rosenblatt 2008). Outlier influence can be mitigated depending on the specific type of outlier. In-plane outliers and bad leverage points can be harnessed using \(\ell_1\)-norm Forero and Giannakis (2012), correntropy or M-estimators (Mandanas and Kotropoulos 2017). Outliers which violate the triangular inequality can be detected and corrected based on their pairwise distances (Blouvshtein and Cohen-Or 2019). Orthogonal outliers are another particular case, where outliers have an important component, orthogonal to the hyperspace where most data is located. These outliers often do not violate the triangular inequality, and thus require an alternative approach.

Height and Volume of n-simplices

We recall some geometric properties of simplices, which our method is based on. For a set of \(n\) points \((x_1,\ldots, x_n)\), the associated \(n\)-simplex is the polytope of vertices \((x_1,\ldots, x_n)\) (a 3-simplex is a triangle, a 4-simplex is a tetrahedron and so on). The height \(h(V_{n},x)\) of a point \(x\) belonging to a \(n\)-simplex \(V_{n}\) can be obtained as (Sommerville 1929), \[ h(V_{n},x) = n \frac{V_n}{V_{n-1}}, \tag{1}\] where \(V_{n}\) is the volume of the \(n\)-simplex, and \(V_{n-1}\) is the volume of the \((n-1)\)-simplex obtained by removing the point \(x\). \(V_{n}\) and \(V_{n-1}\) can be computed using the pairwise distances only, with the Cayley-Menger formula (Sommerville 1929):

\[\begin{equation} \label{eq:Vn} V_n = \sqrt{\frac{\vert det(CM_n)\vert}{2^n \cdot (n!)^2}}, \end{equation}\]

where \(det(CM_n)\) is the determinant of the Cayley-Menger matrix \(CM_n\), that contains the pairwise distances \(d_{i,j}=\left\lVert x_i -x_j \right\rVert\), as \[\begin{equation} CM_n = \left[ \begin{array}{cccccc} 0 & 1 & 1 & ... & 1 & 1 \\ 1 & 0 & d_{1,2}^2 & ... & d_{1,n}^2 & d_{1,n+1}^2 \\ 1 & d_{2,1}^2 & 0 & ... & d_{2,n}^2 & d_{2,n+1}^2 \\ ... & ... & ... & ... & ... & ... \\ 1 & d_{n,1}^2 & d_{n,2}^2 & ... & 0 & d_{n,n+1}^2 \\ 1 & d_{n+1,1}^2 & d_{n+1,2}^2 & ... & d_{n+1,n}^2 & 0 \\ \end{array}\right]. \end{equation}\]

Methods

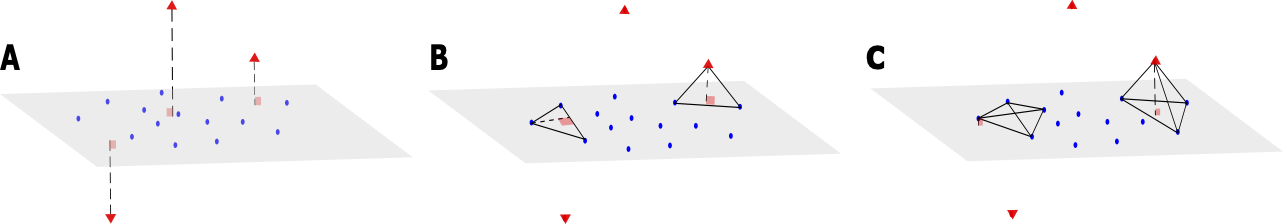

Orthogonal outlier detection and dimensionality estimation

We now consider a dataset \(\mathbf{X}\) of size \(N\times d\), where \(N\) is the sample size and \(d\) the dimension of the data. We associate with \(\mathbf{X}\) a matrix \(\mathbf{D}\) of size \(N\times N\), which represents all the pairwise distances between observations of \(\mathbf{X}\). We also assume that the data points can be mapped into a vector space with regular observations that form a main subspace of unknown dimension \(d^*\) with some small noise, and additional orthogonal outliers of relatively large orthogonal distance to the main subspace (see Figure 1.A). Our proposed method aims to infer from \(\mathbf{D}\) the dimension of the main data subspace \(d^*\), using the geometric properties of simplices with respect to their number of vertices: Consider a \((n+2)\)-simplex containing a data point \(x_i\) and its associated height, that can be computed using equation Equation 1. When \(n<d^*\) and for \(S\) large enough, the distribution of heights obtained from different simplices containing \(x_i\) remains similar, whether \(x_i\) is an orthogonal outlier or a regular observation (see Figure 1.B). In contrast, when \(n\geq d^*\), the median of these heights approximately yields the distance of \(x_i\) to the main subspace (see Figure 1.C). This distance should be significantly larger when \(x_i\) is an orthogonal outlier, compared with regular points, for which these distances are tantamount to the noise.

To estimate \(d^*\) and for a given dimension \(n\) tested, we thus randomly sample, for every \(x_i\) in \(\mathbf{X}\), \(S(n+2)\)-simplices containing \(x_i\), and compute the median of the heights \(h_i^n\) associated with these \(S\) simplices. Upon considering, as a function of the dimension \(n\) tested, the distribution of median heights \((h_1^{n},...,h_N^{n})\) (with \(1\leq i \leq N\)), we then identify \(d^*\) as the dimension at which this function presents a sharp transition towards a highly peaked distribution at zero. To do so, we compute \(\tilde{h}_n\), as the mean of \((h_1^{n},...,h_N^{n})\), and estimate \(d^*\) as

\[\begin{equation} \bar{n}=\underset{n}{\operatorname{argmax}} \frac{\tilde{h}_{n-1}}{\tilde{h}_{n}}. \label{Eq:Dim} \end{equation}\]

Furthermore, we detect orthogonal outliers using the distribution obtained in \(\bar{n}\), as the points for which \(h_i^{\bar{n}}\) largely stands out from \(\tilde{h}_{\bar{n}}\). To do so, we compute \(\sigma_{\bar{n}}\) the standard deviation observed for the distribution \((h_1^{\bar{n}},...,h_N^{\bar{n}})\), and obtain the set of orthogonal outliers \(\mathbf{O}\) as

\[ \mathbf{O}= \left\{ i\;|\;h_i^{\bar{n}}> \tilde{h}_{\bar{n}} + c \times \sigma_{\bar{n}} \right\}, \tag{2}\]

where \(c>0\) is a parameter set to achieve a reasonable trade-off between outlier detection and false detection of noisy observations.

Correcting the dimensionality estimation for a large outlier fraction

The method presented in the previous section assumes that at dimension \(d^*\), the median height calculated for each point reflects the distance to the main subspace. This assumption is valid when the fraction of orthogonal outliers is small enough, so that the sampled \(n\)-simplex likely contains regular observations only, aside from the evaluated point. However, if the number of outliers gets large enough so that a significant fraction of \(n\)-simplices %drawn to compute a height also contains outliers, then the calculated heights would yield the distance between \(x_i\) and an outlier-containing hyperplane, whose dimension is larger than a hyperplane containing only regular observations. The apparent dimensionality of the main subspace would thus increase and generates a positive bias on the estimate of \(d^*\).

Specifically, if \(\mathbf{X}\) contains a fraction of \(p\) outliers, and if we consider \(o_{n,p,N}\) the number of outliers drawn after uniformly sampling \(n+1\) points (to test the dimension \(n\)), then \(o_{n,p,N}\) follows a hypergeometric law, with parameters \(n+1\), the fraction of outliers \(p=N_o/N\), and \(N\). Thus, the expected number of outliers drawn from a sampled simplex is \((n+1) \times p\). After estimating \(\bar{n}\) (from Section 3.1), and finding a proportion of outliers \(\bar p = |\mathbf{O}|/N\) using Equation 2, we hence correct \(\bar{n}\) by substracting the estimated bias \(\delta\), as the integer part of the expectation of \(o_{n,p,N}\), so the debiased dimensionality estimate \(n^*\) is

\[\begin{equation} n^* =\bar{n} - \lfloor (\bar{n}+1) \times p \rfloor. \label{eq:corrected_n} \end{equation}\]

Outlier distance correction

Upon identifying the main subspace containing regular points, our procedure finally corrects the pairwise distances that contain outliers in the matrix \(\mathbf{D}\), in order to apply a MDS that projects the outliers in the main subspace. In the case where the original coordinates cannot be used (e.g, as a result of some transformation or if the distance is non Euclidean), we perform the two following steps: (i) We first apply a MDS on \(\mathbf{D}\) to place the points in a euclidean space of dimension \(d\), as a new matrix of coordinates \(\tilde{X}\). (ii) We run a PCA on the full coordinates of the estimated set of regular data points (i.e. \(\tilde{X}\setminus O\)), and project the outliers along the first \(\bar{n}^*\) principal components of the PCA, since these components are sufficient to generate the main subspace. Using the projected outliers, we accordingly update the pairwise distances in \(\mathbf{D}\) to obtain the corrected distance matrix \(\mathbf{D^*}\). Note that in the case where \(\mathbf{D}\) derives from a euclidean distance between the original coordinates, we can skip step (i), and directly run step (ii) on the full coordinates of the estimated set of regular data points.

Dataset

The Human Microbiome Project (HMP) (Turnbaugh et al. 2007) dataset represents the microbiome measured across thousands of human subjects. The human microbiome corresponds to the set of microorganisms associated to the human body, including the gut flora, or the skin microbiota. The data used here corresponds to the HMP1 phase of clinical production. The hypervariable region v13 of ribosomal RNA was sequenced for each sample, which allowed to identify and count each specific microorganism, called phylotype. The processing and classification were performed by the HMP using MOTHUR, and made available as low quality counts (https://www.hmpdacc.org/hmp/HMMCP/) (Turnbaugh et al. 2007). We downloaded this dataset, and subsequently, counts were filtered and normalized as previously described (Legrand 2017). For our analysis, we also restricted our dataset to samples collected in nose and throat. Samples and phylogenies with less than 10 strictly positive counts were filtered out (Legrand 2017), resulting in an \(n \times p\)-matrix where \(n=270\) samples and \(p=425\) phylotypes. Next, the data distribution was identified with an exponential distribution, by fitting its rate parameter. Normalization was then achieved by replacing the abundances (counts) with the corresponding quantiles. Lastly, the matrix of pairwise distances was obtained using the Euclidean distance.

Results

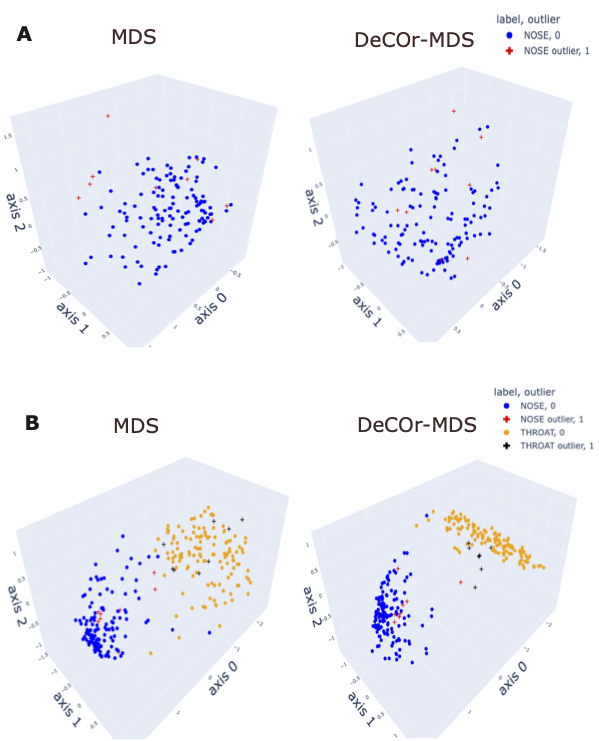

To assess our method incrementally, we restricted first the analysis to a representative specific site (nose), yielding a \(136 \times 425\) array that was further normalized to generate Euclidean pairwise distance matrices (see Section 4 for more details). Upon running DeCOr-MDS, we estimated the main dimension to be 3, with 9 (6.62%) orthogonal outliers detected, as shown in Figure 2.A. This is also supported by another study that the estimated dimension of HMP dataset is 2 or 3 (Tomassi et al. 2021). We also computed the average distance between these orthogonal outliers and the barycenter of regular points in the reduced subspace, and obtained a decrease from 1.21 when using MDS to 0.91 when using DeCOr-MDS. This decrease suggests that orthogonal outliers get corrected and projected closer to the regular points, to improve the visualization of the data in the reduced subspace. In Figure 2.B, we next aggregated data points from another site (throat) to study how the method performs in this case, yielding a \(270 \times 425\) array that was further normalized to generate Euclidean pairwise distance matrices. As augmenting the dataset brings a separate cluster of data points, the dimension of the main dataset was then estimated to be 2, with 13 (5%) orthogonal outliers detected, as shown in Figure 2.B. The average distance between the projected outliers and the barycenter of projected regular points are approximately the same when using MDS {(1.46)} as when using DeCOr-MDS (1.45) for nose, and are also approximately the same when using MDS (1.75) to when using DeCOr-MDS (1.74) for throat. This decrease also suggests that orthogonal outliers get corrected and projected closer to the regular points.

The Python scripts for generating the results are available at this repository.